When we talk about disconnected systems, we tend to imagine a binary state—something either connected or not.

But that’s not how the real world works.

Disconnection is not a fixed category. It’s a moving target shaped by mission needs, geography, infrastructure, policy, and even weather. The people who operate in those environments are just as varied as the systems they depend on.

Who Are We Building For?

Disconnected environments aren’t theoretical. They’re lived realities—places where people need to get real work done with constraints that most cloud-native assumptions ignore.

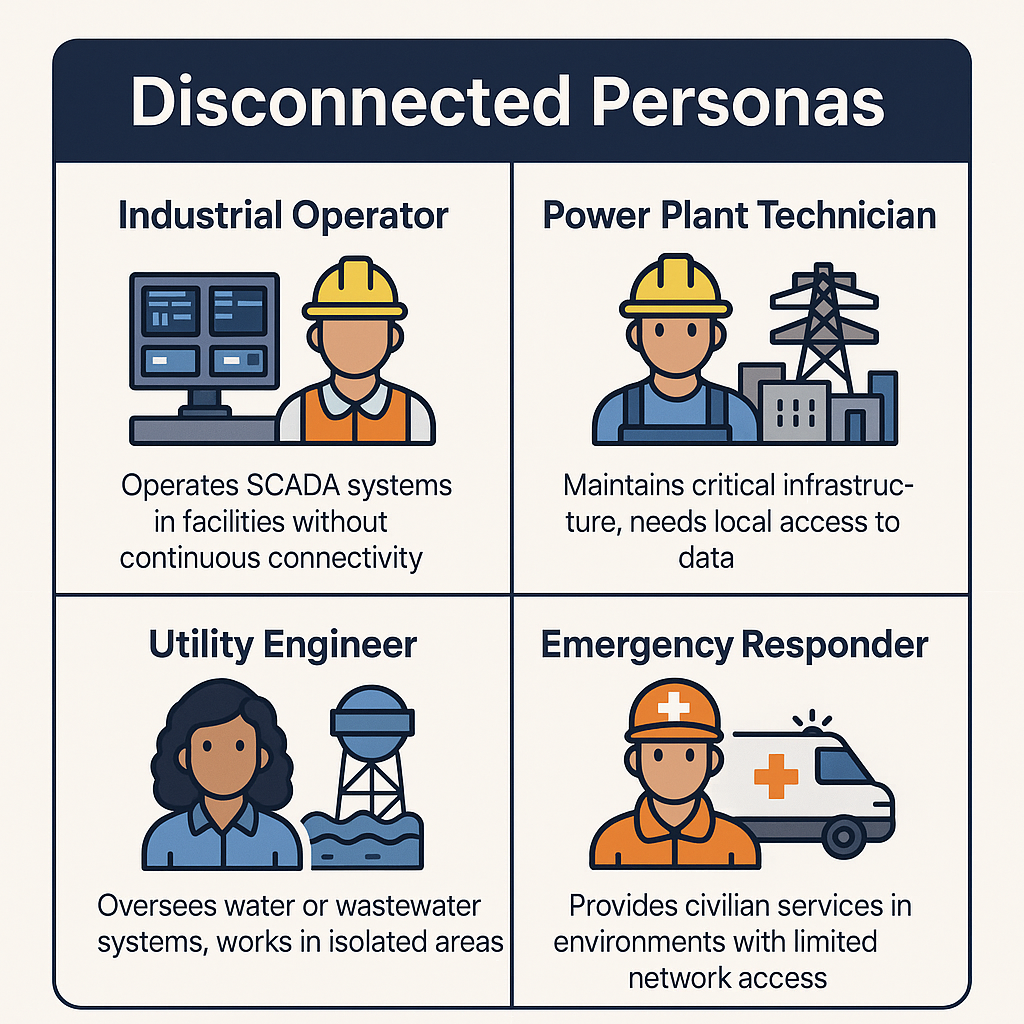

Across sectors—defense, industrial, civilian—we see recurring personas, each grappling with versions of the same core problem:

How do you operate modern systems when connectivity is partial, delayed, or entirely absent?

Here are some of the most common personas we encounter:

The Field-Deployed Operator

Where they work: Submarines, forward operating bases, scientific expeditions, deep-sea rigs.

Constraints:

- No internet access for extended periods (days or weeks).

- Disconnected by design, not by accident.

- Require fully self-contained systems with no reliance on cloud APIs.

Needs:

- Prepackaged updates and infrastructure.

- Resilient local logging and observability.

- Secure local identity and access control.

The Sync-Window User

Where they work: Drone hubs, expeditionary networks, disaster relief centers, rural deployments.

Constraints:

- Limited, intermittent connections via satellite or sneaker-net.

- Syncs may be timed, bandwidth-constrained, or unpredictable.

Needs:

- Partial sync support with resumable updates.

- Version drift tolerance across clusters or nodes.

- Workflow automation that can queue and apply changes asynchronously.

The Regulated Enclave Engineer

Where they work: SCIFs, contractor enclaves, nuclear facilities, defense labs.

Constraints:

- Internet-restricted but internally networked.

- Changes flow through policy, review, or manual approval gates.

- Even airgapped systems may use data diodes or tightly controlled ingress/egress.

Needs:

- Transparent auditability of software supply chain.

- Approval-based CI/CD pipelines.

- Repository mirroring and artifact pre-seeding.

The Industrial Controls Maintainer

Where they work: Power plants, water treatment facilities, manufacturing floors.

Constraints:

- Legacy OT networks segmented from IT environments.

- Cyber-physical systems sensitive to downtime or update errors.

- SCADA systems often isolated for security, not bandwidth.

Needs:

- Zero-downtime deployments to critical systems.

- Offline-capable monitoring and alerting.

- Airgapped patching and update strategies.

The Civil Infrastructure Technologist

Where they work: Municipal services, smart city infrastructure, rural healthcare, public transit systems.

Constraints:

- Inconsistent broadband or cellular access.

- Budget and personnel limitations.

- Devices and sensors spread across wide geographies.

Needs:

- Lightweight, resilient software footprints.

- Low-touch management for edge devices.

- Secure remote diagnostics—even when “remote” is delayed.

What Makes This Hard?

Most cloud-native tooling was built with always-on, high-bandwidth environments in mind:

- It assumes access to public image registries.

- It relies on federated internet identity.

- It pulls from external APIs and SaaS services as a default.

These assumptions don’t hold in disconnected environments—and breaking them can cripple otherwise promising solutions.

But it’s not just about what we assume. It’s about what we haven’t planned for.

The Future of “Connected” Is Uncertain

We don’t know what the next wave of disconnected use cases will be:

- IoT deployments syncing inference models from rural edge sites.

- Industrial robotics running real-time control loops with local failover.

- Nations implementing sovereign internet policies.

- Community networks providing essential services through mesh relays.

The edge is expanding. The definitions are blurring. And “cloud native” is being stretched to meet those realities.

Designing for a Moving Target

Disconnection forces hard design questions up front:

- Can this system run without phoning home?

- Can it catch up after being offline?

- Can it verify changes in an isolated environment?

If the answer is “no,” you’ve uncovered a fragility—one that may surface in your production environment, or in tomorrow’s new deployment zone.

Here’s the more critical question:

Can your system tolerate disconnection—even if it’s not disconnected today?

Summary

Disconnection is not a binary. It’s a spectrum that spans sectors, geographies, and missions.

The people working in these environments are already adapting to that spectrum. As builders, we have to meet them where they are—and anticipate where they’re going.

What’s niche today could become the norm tomorrow. The assumptions we make now about connectivity will define the resilience of our systems when those assumptions fail.

Want to go deeper?

- Check out the Zarf project for building packages that run across the spectrum

- Join the

#zarfchannel in Kubernetes Slack - Or hit me up on socials to chat about the weirdest places you’ve deployed an app